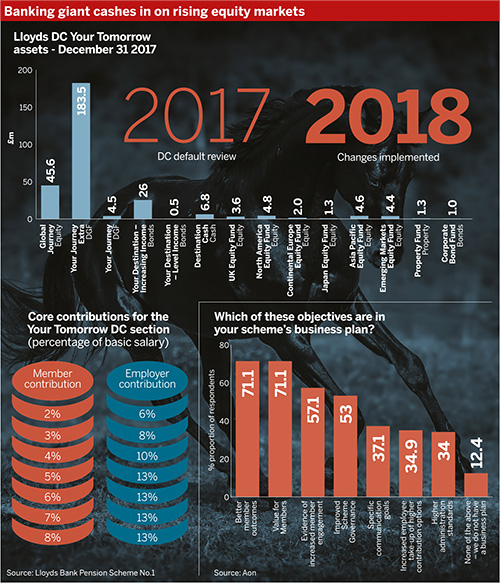

Trustees of the Lloyds Bank Pension Scheme No.1 have overhauled the default offering for defined contribution members, ditching a diversified growth fund for a 100 per cent equity allocation in the first years of saving.

Bucking an emerging trend to derisk members towards drawdown, the scheme also opted to focus the majority of its default portfolio on annuity purchase in the run-up to retirement.

The move followed an in-depth formal review of the DC investment strategy that assessed risk, returns and the membership profile. Changes were made in March this year.

Around 85 per cent of DC plan members are in the default fund, according to Aon research.

DGFs and other multi-asset strategies in defaults have come under increased scrutiny, as they have failed to keep pace with cheap tracker funds in unusually benign equity markets.

Lloyds’ review considered the aims of the default arrangement, the investment returns – net of charges, the membership profile, security of assets and benchmarks for similar funds, the scheme’s latest annual report shows. Trustees also considered the effect of freedom and choice.

The most important risk in DC is not volatility, it’s shortfall risk

Maria Nazarova-Doyle, JLT Employee Benefits

Lloyds opts for equities over DGFs for first phase

Changes were subsequently made in 2018. The default arrangement had previously invested in the Your Journey Extra DGF in accumulation, switching over to bonds and cash 10 years before retirement.

The Your Tomorrow DC plan’s new arrangement invests 100 per cent in a global equity fund until a member is 30 years from retirement. Over the next 10 years it gradually switches into a mixed investment fund, where it remains until the member is 10 years from retirement.

Over the last decade, the default switches into an Annuity Focus Fund, with a partial switch into a cash fund also taking place in the final 3 years. By the member’s target retirement date, the allocation is 20 per cent in the mixed investment fund, 65 per cent in the Annuity Focus Fund, and 15 per cent cash.

The main aim of the default change was to reduce volatility and the associated risk that members’ accounts drop quickly and substantially in the run up to retirement, according to the annual report.

The trustees informed members of the changes in November last year.

“Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustees monitors fund performance on an ongoing basis and works with its appointed investment adviser to secure the best outcomes for members,” said the trustee.

“These outcomes include investment returns, appropriate risk profiling and the flexibility to amend the fund allocation to reflect economic opportunities and to flex asset allocation and risk profiles as members move closer to retirement,” the trustee added.

“The recent changes to the default funds for the Your Tomorrow section of the Lloyds Bank Pension Scheme No.1 reflect this process, which was carried out alongside the trustee of the Your Tomorrow pension scheme.”

Focus on performance

Trustees reviewing their default strategy should focus on two broad areas, starting with the performance of each component of the fund, according to Mark Futcher, head of workplace wealth at consultancy Barnett Waddingham.

With a blended white-label fund, for example, “you will have to look not just at the headline figures of the performance of that blended fund, but also the individual constituent parts – is the equity manager doing what it should be doing? Is the property manager doing what they should be doing?”

Schemes might also take stock of new investment opportunities. “Bigger pension schemes… will be able to start getting access to some of those newer investment classes like infrastructure,” Futcher noted.

Tackling shortfall risk

The Lloyds trustees’ decision to replace the DGF with a global equity fund for the beginning of their member journey comes following a bull run in equity markets, coupled with low volatility, which has generally impacted DGF performance.

“DGFs haven’t performed as well as trustees had hoped, and they’ve struggled in this very bull, rising market, that equities have seen over the last 10 years or so,” said Lydia Fearn, head of DC and financial well-being at consultancy Redington.

DGFs are designed to manage risk and hold their own amid periods of volatility. But with equities storming, DGFs have lagged behind, she said.

This has prompted many trustees to think about what it means for member outcomes, and whether there is a place for equities in their strategy to produce better long-term outcomes.

A lot will depend on future market volatility and equity performance. “Who knows what’s going to happen in the next few years with Brexit, and the uncertainty, and whether – in that environment – DGFs might actually do pretty well,” Fearn said.

“It’s thinking about where do you want that risk mitigation, and where in the glidepath you need it.”

For younger DC members who do not necessarily have much in their savings and have a long time until they reach retirement, “putting them into a lower-cost global equity fund is probably better for them potentially, in the long run”, Fearn noted.

She advised schemes to think about their investment design on a regular basis to try and work out whether the strategy is right for members at that point in time.

Similarly, Maria Nazarova-Doyle, senior investment consultant and head of DC investment consulting at JLT Employee Benefits, highlighted the danger of people not having enough money when it comes to retirement. “The most important risk in DC is not volatility, it’s shortfall risk,” she said.

Member behaviour still shifting after freedoms

There is also the overriding question of whether the default fund is suitable for the majority of members.

Before the introduction of pension freedoms, more than 90 per cent of pots were used to buy annuities – but drawdown has become a lot more popular. The Financial Conduct Authority’s Retirement Outcomes Review interim report in 2017 highlighted that twice as many pots are moving into drawdown than annuities.

“There’s no longer a clear majority,” said Futcher, adding that assessing the suitability of the default fund not only involves focusing on its performance but also on its purpose, in terms of how members are likely to take their money.

“A lot of schemes rushed to make a decision [on their default fund] post-freedom and choice, on the basis that people weren’t going to buy an annuity,” Futcher noted.

This often entailed changing the endpoint to cash. But many schemes made this big change without really knowing anything about members’ long-term behaviour, he said.

Now schemes are starting to question whether that was the right thing to do. “We are starting to see the emergence of maybe some more longer-term behaviour coming through from DC members,” Futcher said.

Multi-faceted approach

The changes made by the Lloyds trustees involved a significant transition process. The scheme wrote to members, advising them that they were making changes to where members can invest their savings, with the aim of boosting investment performance, while simplifying the combination of investment options available.

In the update, the trustees noted the transaction costs for moving the money and changing the funds were “very small”.

It said they will incur additional one-off transaction costs estimated to be between zero and 0.5 per cent, depending on the fund, equivalent to up to 50p for every £100 of savings being moved.

Steve Charlton, SEI’s DC managing director, EMEA, said there are several factors for trustees to consider when dealing with any sort of change.

Communication and administration are important. “You’re telling your members that you’re going to make a change – you’re explaining the rationale,” he noted.

At the same time, “you’re looking at the data, looking at the member records and mapping from one place to another”, he said, adding that “the bigger the scheme, the greater the challenge”.

When it comes to transitioning the money, “you’ve got the funds where that money is coming from… you’ve got the funds where that money is being reinvested, you’ve got to try and match the dealing cycles of the funds so that you can avoid any out-of-market exposure as far as possible”, Charlton noted.

Keep member options open

Ultimately, trustees must consider the potential ramifications of the physical process of moving money, as well as the “intellectual challenge of, ‘What are we moving and why are we moving it?”, according to Charlton.

He said many schemes are between a rock and a hard place, “because not enough time has passed… for them to be able to identify what the membership is actually doing”.

This inability to predict member behaviour often leads to schemes setting a less specific approach, according to Nazarova-Doyle.

She noted that “more schemes are trying to basically make the investment strategy towards later years a bit less precise, because we don’t know what members are going to be doing, and when they’re going to be doing it”.

Even members tend to not know what they want, Nazarova-Doyle added. “So, a really good approach to the default design is to try and keep their options open from an investment point of view.”