Data crunch: As pension schemes continue to mature, their investment strategies are becoming increasingly similar to those of insurance companies. Given that schemes do not face the same regulatory constraints as insurers, some experts say it makes sense to take advantage of the greater freedoms available to them when they are at earlier stages of their development.

Indeed, pension funds have one major advantage over insurance companies: they are not bound by the solvency capital requirements that can penalise insurers for taking on greater credit risk and the chance of greater returns.

Making smaller allocations to higher-yielding (typically sub-investment-grade) credit can enhance portfolio returns without unduly impacting risk metrics

Pete Drewienkiewicz, Redington

Pension investors rarely face such problems when constructing their portfolios. But some are slow to use their greater flexibility in their choice of credit quality, structured products and derivatives, and managing portfolio turnover, according to JPMorgan Asset Management.

In it latest Pension Pulse report, JPMAM says that if pension funds are not taking advantage of the spectrum of buy and maintain options available that have long been used by insurers on a more constrained basis, they might be missing a trick.

Capture return opportunities

Jerry Song, an associate in JPMAM’s EMEA pensions solutions and advisory team, suggests that schemes could use “a higher proportion of BBB-rated credit and securitised assets in their allocation while actively managing the higher credit migration risk”.

In this way “pension funds could capture incremental return opportunities as part of their journey towards their long-term goal”, he says.

This is potentially a big plus since approximately half the global investment-grade market is rated BBB, although the risk of default is greater than with top-grade bonds.

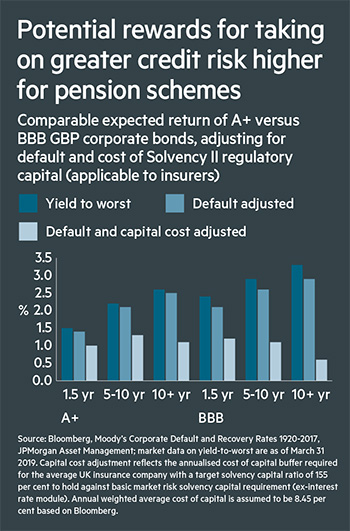

The potential rewards for taking credit risks can be significant, according to JPMorgan: over 1 to 5 years the expected surplus return on A+ bonds is 0.2 per cent while for BBB 1 to 5 year bonds it is four times as high at 0.9 per cent.

However, its analysis indicates that, in an average year, around 5 per cent of BBB-rated bonds migrate to sub-investment-grade, and in an average recession scenario that proportion increases to around 15 per cent.

"Making smaller allocations to higher-yielding (typically sub-investment-grade) credit can enhance portfolio returns without unduly impacting risk metrics,” says Pete Drewienkiewicz, Redington’s chief investment officer, global assets.

He has also found that portfolios of higher-yielding assets recover more quickly from market shocks than investment-grade portfolios.

There are also other ways to achieve liability-aware buy-and-maintain objectives says Mr Drewienkiewicz, citing real asset types of investments – including renewable infrastructure, ground rents, and long-lease real estate.

Covenant caveat

Others are more cautious. Francis Fernandes, senior adviser at covenant specialists Lincoln Pensions, says: “While DB pension schemes can benefit from operating free from solvency and accounting restrictions, the asymmetry of outcomes facing members means that many trustees are unlikely to take more investment risk than they believe is necessary.”

He adds: “A DB scheme’s greatest strength is the employer covenant (which people often forget stands behind any risks run in a scheme's asset portfolio).

Where the employer covenant is robust, trustees might be able to justify being more brave in their investment decisions – or get additional funding – in order to reach their endgame more quickly he says. “But the covenant can also be a DB scheme’s greatest weakness.”

Buyouts are often the ultimate answer for companies that do not want the millstone of long-term liabilities around their necks, but illiquidity and Solvency II-unfriendly investment may limit any ability to access a competitive buyout from an insurer.

Sammy Cooper-Smith, business development at Rothesay Life, warns that if “pension schemes adopt this approach and specifically target investment instruments that are unavailable to insurers, maintaining liquidity on those assets is vital if their long-term exit plan includes buying an annuity.”

Time to move towards CDI

The time for traditional growth strategies seems over for many pension schemes and a focus on liabilities is more appropriate as pension schemes become more insurance-like.

Charles Cowling, chief actuary at Mercer, agrees that schemes “are definitely taking a page from insurers’ playbooks”.

He advocates cash flow-driven investment. As funding levels improve and with CDI strategies more widely available, pension funds should embrace them, he says.

Mr Cowling adds that they carry far less risk than the traditional growth-based investment strategies favoured by many schemes.

He concludes: “The question that trustees of pension schemes with exposure to growth [equity] assets should be asking at this time of political and market uncertainty is: if the pension scheme objectives [to deliver members’ benefits] can be achieved with far less risk, why are we not urgently moving towards a CDI strategy?”