The pension scheme for MPs is not doing enough to combat the risks posed by climate change, according to a divestment campaign backed by more 360 current and former parliamentarians.

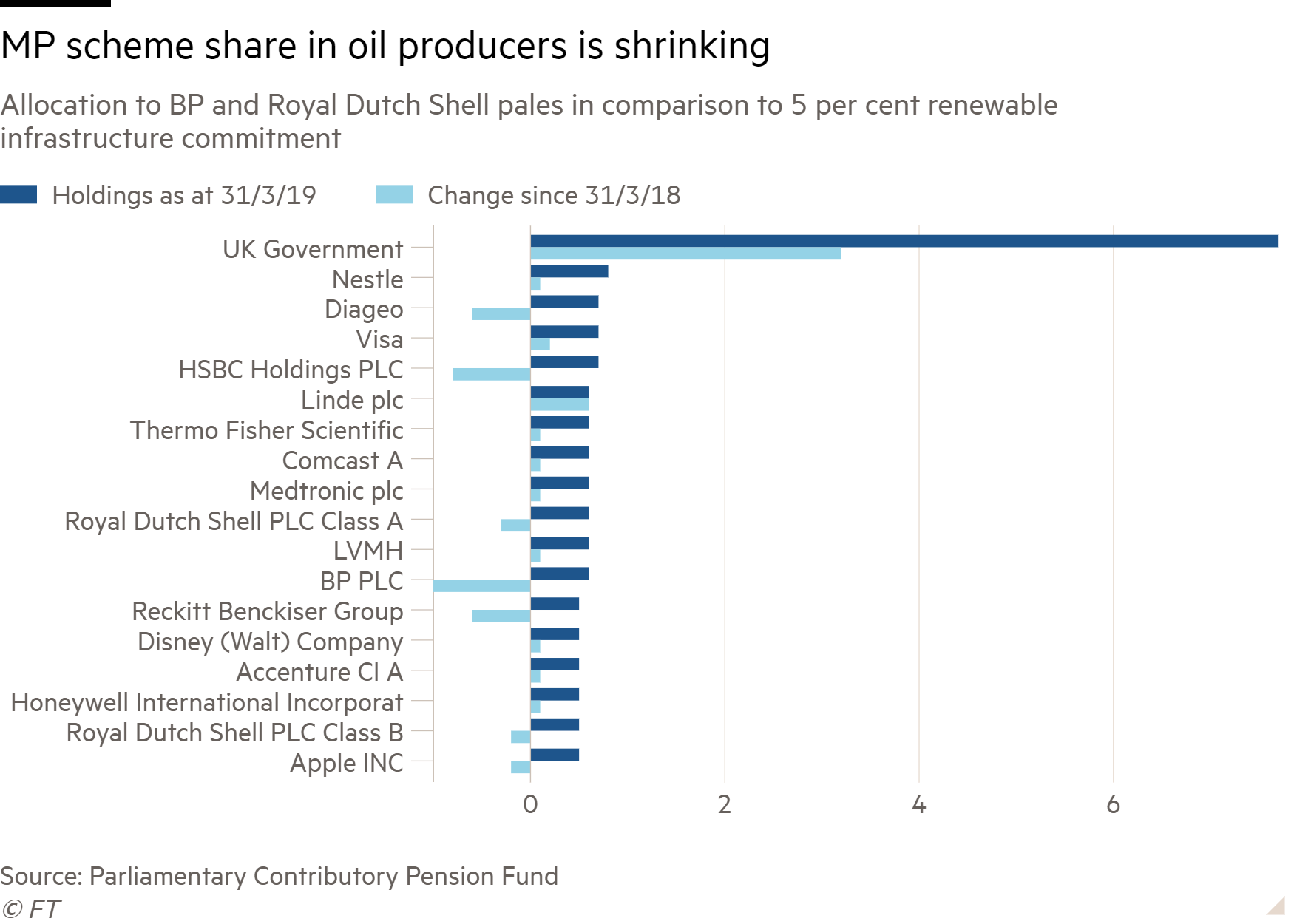

Campaigners welcomed the decision of the £733m Parliamentary Contributory Pension Fund to allocate 5 per cent of scheme assets to renewable energy infrastructure, but said this was of limited benefit when the scheme retains investments in carbon-intensive companies such as BP and Royal Dutch Shell.

The scheme’s allocations to these fossil fuel extractors has fallen over 2018 and 2019, with exposure to BP falling by 62 per cent and Shell by 26 per cent. Combined, the two energy giants account for just more than 1 per cent of the portfolio.

In addition to the renewable allocation with BlackRock, which will focus on solar and wind projects, the trustee board agreed in February this year to switch its current market cap-weighted equity funds with the fund giant to low-carbon strategies. Meanwhile, 30 per cent of its existing equity portfolio will be diverted into a Schroders global sustainable multi-factor strategy.

These investments cannot be justified on ethical, environmental or financial grounds, and they undermine MPs’ credibility in addressing the climate emergency

Caroline Lucas, Green party MP

The scheme’s annual report also boasted of the fund’s dedicated responsible investment policy and status as a signatory to the UK Stewardship Code. It said trustees regularly monitor managers’ engagement activities with investee companies, questioning them on any apparent irregularities.

However, Divest Parliament campaigners and the MPs supporting them have said these steps are not enough.

MPs call for total divestment

Caroline Lucas, Green party MP for Brighton Pavilion, said: “Investing in clean energy is clearly the right thing to do, financially and for the future of our planet, so I’m glad the Parliamentary Pension Fund is doing this. But it has to also stop investing in Shell and BP.”

Ms Lucas said the fund’s strategy of tilting and engagement was incompatible with the climate emergency declared by parliament in 2019.

“These investments cannot be justified on ethical, environmental or financial grounds, and they undermine MPs’ credibility in addressing the climate emergency. They have to stop,” she said.

While the support of dedicated climate campaigners like Ms Lucas is unsurprising, Divest’s pledge has also been signed by all of the Labour leadership candidates, and significant numbers of current Conservative party politicians feature among its list of backers. According to the campaign, strong support has been garnered from MPs joining the scheme after the last general election.

Pensions and financial inclusion minister Guy Opperman has urged trustees to support the growth of sustainable business and green energy with their investments.

In early drafts of regulations governing statements of investment principles, the government mulled a requirement for pension schemes to ascertain and consider member views on sustainability when setting their investment strategy.

The Department for Work and Pensions has confirmed its intention to introduce reporting in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. In a speech in Edinburgh earlier this month, Mr Opperman called climate change “the defining issue of the 21st century”, adding: “On this issue I am unquestionably in a hurry. I’m expecting the regulator to take decisive action.”

Mark Campanale, founder of think-tank the Carbon Tracker Initiative, said: “2020 must mark a decisive turning point where trustees of private and public pension funds stop fuelling the fire of the climate crisis through their business-as-usual investments in fossil fuel majors.

“Some of these companies present grave risks to people’s pensions, as coal, oil and gas risk becoming ‘stranded assets’ as countries align policy with containing global heating to 1.5C and the cost of clean energy continues to plummet,” he continued.

“Even the Bank of England now plans to exclude fossil fuel assets from its purchases.”

Divestment debate ‘not black and white’

The pressure for divestment faced by the PCPF marks it out from most other private sector schemes, where the prevailing investment wisdom has been that remaining invested and engaging with ‘sin stocks’ is a more powerful driver of change.

But the scheme is among a significant group of plans where the political pressure surrounding their sponsor can mean trustees are forced to take a different approach.

Pete Smith, principal and senior investment consultant at Barnett Waddingham, said: “For the pension schemes of many organisations that have declared climate emergency, the conundrum facing the MPs’ pension scheme is familiar.

“The use of pooled funds to reduce costs hinders the flexibility to divest completely from specific companies. For all but the largest schemes, it is too simplistic to say simply divest.

“The tools to do so need to be available in all asset classes, not just equities. At present they are very limited. Likewise, the ability of pooled fund users to drive change in specific companies through engagement is also limited.”

If trustees do decide to divest from fossil fuels, they then face a significant number of decisions as to how to implement their policy.

“To divest from fossil fuels is not a binary issue. There are a number of different considerations that need to be thought about quite carefully,” said Jennifer O’Neill, senior investment consultant in Aon’s environmental, social and governance and responsible investment practice.

One pitfall she highlighted is trustees assuming that by eliminating prominent fossil fuel extractors, they will solve their climate change problem. In fact, the carbon intensity of a portfolio is affected by companies throughout the value chain.

“Too often the discussion about divesting is focused on the oil and gas sector in isolation, without perhaps looking at the broader picture,” Ms O'Neill said.

“The first question is why, what is it that the trustee board wishes to achieve.”