Volatility made its grand return to many of the key markets in which pension funds invest assets towards the end of 2018, driven by geopolitical instability and fears that the end of a long business cycle may finally be nigh. 2017 seems a long way away. Angus Peters explores reasons to be cheerful despite the gloomy outlook.

Global GDP grew at a rate of 3.7 per cent in 2018 and, according to the International Monetary Fund, will remain at much the same level into the 2020s, albeit with a gradual slowdown in advanced economies.

Instead it is questions over the resilience of the economy to this slowdown, along with political unrest, that have hackles raised in the markets.

To get a decent return you’ve got to be invested but with all these unknowns out there, probably the risk is a bit higher than it has been

Andrew Wauchope, Psigma Investment Management

Central banks might have to lower base rates into negative territory to provide the same stimulus as they did in response to previous recessions, while global debt has risen steadily. Add to that an ongoing trade war between the US and China, tensions between eurozone countries and asset prices that are still high by historical standards, and it becomes easier to see why allocation is now a slight headache.

“Markets… are just looking relatively fully valued and there’s a lot happening. There’s no obvious sign of a trigger for a fall, it’s just that it’s not looking great value at the moment,” says Andrew Wauchope, senior investment director at Psigma Investment Management.

“To get a decent return you’ve got to be invested, but with all these unknowns out there, probably the risk is a bit higher than it has been,” he adds.

With its prediction of a possible recession in 2020, Psigma is therefore putting an emphasis on maintaining a comfortable cash buffer and seeking diversification, albeit with a focus on liquidity limiting its exposure to both alternatives and longer-duration credit.

Equities

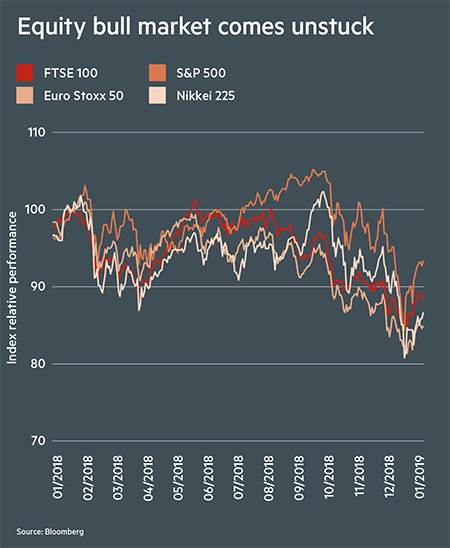

2018 has been a year to forget for many equity investors. The FTSE All-World index finished 2018 down by 11.5 per cent, its worst year since the global financial crisis in 2008, reflecting a torrid year for UK, US and European shares. Neither have active fund managers flourished amid the returning volatility and pain for passive investors – stockpickers have seen massive outflows, and a PwC report in November predicted that a quarter of active funds would disappear by 2025, with a fall in fees of nearly one-fifth.

With central bank support and cheap borrowing coming to an end, global managers must now pick companies able to weather these storms. In domestic markets, the question is heavily impacted by Brexit. Smaller companies with less overseas earnings have been shunned by investors and, according to Schroders, will perform best in the event that the UK achieves a deal with the EU.

“This would be particularly beneficial to those UK domestic companies that have suffered a severe derating over the past two-and-a-half years,” says Sue Noffke, a UK fund manager at the company.

“UK-focused banks, property companies, housebuilders, consumer discretionary areas (general retailers and leisure companies), food retailers, media agencies and utilities are all trading on depressed ratings.”

Schemes look longer for returns

Translating these fund manager concerns into pension fund strategy, trustees are fortunately not bound by the same liquidity constraints.

A number of managers and investment consultants identify long-dated credit assets as particularly attractive, while large defined contribution schemes, arguably the least constrained in the UK system, are looking to tie up capital beyond the confines of bond and equity markets.

“Towards the back end of 2018 and looking forward we’re seeing a lot more volatility than we’ve seen in the past, so it’s a more challenging environment,” says Paul Todd, director of investment development and delivery at master trust Nest. “[That is] precisely why we’ve always been very keen to have a well-diversified portfolio.”

Most of my clients are moving away from the more complex, relative-value approaches to DGFs

Laura Myers, LCP

Across almost its entire range of target date funds, Nest has added emerging markets, listed property, hybrid property, commodities, and climate aware stocks to the traditional equity-bond mix still employed by some DC schemes. The scheme controls volatility in the early stages of savers’ membership to discourage opt-outs.

Commodities were introduced as an inflation hedge in 2018, and a request for proposals asked managers of illiquid mid-market corporate loans, real estate debt and infrastructure debt to deliver a pricing model more appropriate for auto-enrolment savers.

“A lot of the DC schemes over the past 10 years have been very exposed to equities,” says Mr Todd. “What’s your plan for when equities don’t always perform well? There have been long periods in history where they’ve performed quite poorly.”

There is, however, a limit to Nest’s appetite for volatility control, as this is ultimately the engine for members’ long-term gains, and Mr Todd states a preference for “good, managed risk”.

The scheme will not look to smooth out returns via expensive active managers in efficient markets such as equities for example, preferring to investigate the possibility of smart beta indexes to boost its stock portfolios.

Smaller schemes follow suit

This philosophy of diversification to manage volatility is likely to be replicated among the large number of smaller, single-employer trusts that make up the other side of the UK’s DC infrastructure.

The key difference between large and small schemes has historically been that, due to a lack of scale, smaller plans have only been able to achieve diversification via an asset manager offering one of the many types of diversified growth fund.

“Most of my clients are moving away from the more complex, relative-value approaches to DGFs,” says Laura Myers, head of DC at consultancy LCP.

Fixed income

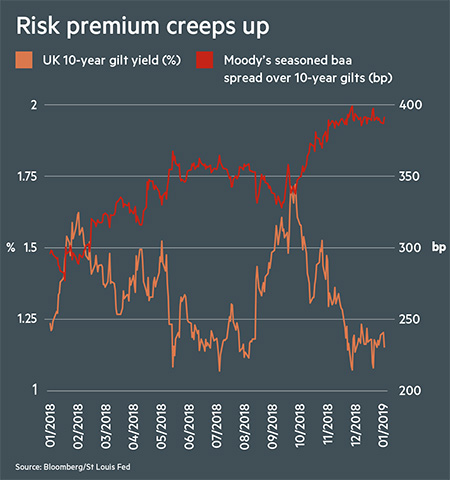

If bonds have sometimes rescued investors when equity returns have soured, 2018’s losses across a range of fixed income assets showed that pension schemes cannot necessarily rely on this negative correlation.

Gilt yields, which hold a double significance for DB schemes owing to their impact on scheme liabilities, fell at all maturities in December after gains earlier in the year, failing to offset declines in total scheme asset values. That meant that trustee hopes that the Bank of England’s gradual tightening of monetary policy would lift them out of deficit were proved fanciful – UK schemes fell out of surplus over December on the Pension Protection Fund’s measure.

Yields did lift, and spreads widened, in corporate bond markets. That meant a loss for bondholders over the period, but some managers see the bright side.

“We’ve seen spreads tighten quite a lot over the past five years,” says Axa IM’s Lionel Pernias. “Now that we see spreads widen there are lots of opportunities in the market, especially when you go into global credit portfolios.”

In many cases DGFs were sold on the promise of ‘equity-like’ returns with lower volatility. Having failed to keep pace with equity markets over the past few years, some schemes have run out of patience and will not test them in choppier waters.

“We’ve seen that most of the DGFs have held up a little bit better than equities,” says Ms Myers, but she adds that “trustees are still quite disappointed”.

Instead, she says, many are opting for “DIY” diversification, gaining exposure to property, commodities and listed infrastructure at a lower cost via investment platforms. In a virtuous cycle, Ms Myers says managers are reducing fees on new and existing products.

Not all alternatives are created equal, and both defined benefit and DC schemes would do well to avoid assuming that they achieve diversification. Odi Lahav, chief executive of consultancy MJ Hudson Allenbridge, says UK real estate looks unattractive due to the lower forecast for economic growth in the country – the same factor that is shaking up domestic equities.

The increased popularity of some diversifying investments has also meant that their returns may look expensive. However, price is not everything. Mr Lahav says infrastructure equity is afflicted by a permanent mismatch of supply and demand, but that its inflation-proofing characteristics mean it is “still such an attractive proposition”.

Similarly, he notes that while private equity valuations are stretched, the inherent ability of managers to hold dry powder and deploy it when, for example, a recession arrives and assets are cheap, makes it an appealing choice. Mr Lahav warns against private equity secondaries, where funds of funds have increased leverage to maintain returns.

Beware the 'B' word

If pension schemes are by their very nature long-term investors and happy to lock up capital, it will nonetheless be tempting to focus on the Brexit upheaval currently engulfing many aspects of British life.

The outcome of this crisis could have a significant impact on the portfolios of UK pension funds, not least because any of the Brexit outcomes is likely to be met by fluctuations in the value of sterling relative to other currencies.

Brexit is a risk like the many risks on the table – and I don't believe anybody has a clue on the likely directionality of risk assets or long interest rates given the various scenarios that could play out on Brexit over the next two months or so

Steve Delo, Pan Governance

Keeping an eye on the long term will not be enough for those DB schemes unfortunate enough to need to agree new funding plans this year.

Steve Delo, independent trustee and managing director of Pan Governance, says: “With equity markets having sold off a bit, and anything possibly happening by March 29 on Brexit, it is entirely possible that those schemes with end first-quarter actuarial valuations will have some disappointing numbers to deal with. I suspect some 2019 valuation negotiations could be tricky.”

The potential for sterling to whipsaw has at least been mitigated in some cases. Most DB schemes currently hedge between 50 and 100 per cent of their foreign exchange exposure, according to currency specialists Millennium Global Investments.

“We see some potential for upside against the dollar,” says Claire Dissaux, head of global economics and strategy at Millennium. She explains that given the Bank of England’s bias towards tightening policy if Brexit uncertainties abate, and the market’s unwillingness to price this in, the currency has the potential to appreciate.

That would be good news for those DB sponsors reliant on imported goods, but less so for the global assets of their pension schemes if they are not hedged. Mr Delo says trustees should only tolerate the amount of downside risk in their funding and investment strategies that their covenant can bear.

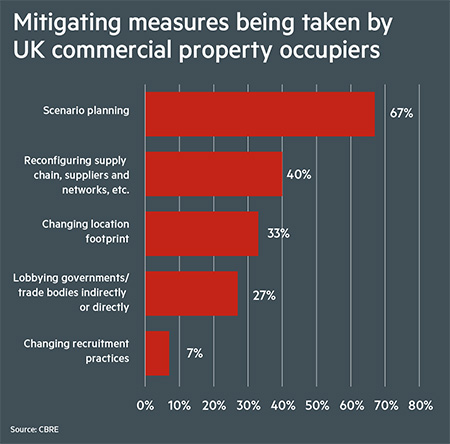

Real estate

One asset class that might feel the impact of Brexit instability is real estate. The asset has proved popular with investors but yields have steadily decreased in recent years. Add to that the prospect of companies relocating staff to Europe in the aftermath of the UK’s exit from the EU, and the outlook for commercial property in particular looks gloomy.

Tom Brown, managing director of real estate at Ingenious, says: “What started in June 2016 as a political and constitutional crisis has spread into the wider economy. In response, investors seem to be waiting for greater clarity before committing their cash. In property markets, transaction volumes have reduced on account of a mismatch between vendors and purchasers’ expectations.”

Residential property at least has a shortage of supply fuelling returns, but Aviva Investors says it thinks the housing market will continue to cool.

Senior research analyst Jonathan Bayfield says a defensive approach is best, and tips offices in large cities as an attractive area over the next five years: “As capital values are hit, rental growth is likely to be the only source of outsized returns in 2019 and beyond.”

“Brexit shouldn’t massively change anything that astute trustee boards are doing on DB investment,” he says. “Brexit is a risk like the many risks on the table, and I don’t believe anybody has a clue on the likely directionality of risk assets or long interest rates given the various scenarios that could play out.”

Where sponsors are exposed to the impact of Brexit, trustees may look to accelerate hedging plans, says Mr Delo, adding that boards should understand their value at risk.

Nick Lewis, director of investment consulting at Redington, agrees. “Don’t try and call it,” he says.

“It’s definitely something to consider. I think you shouldn’t be derisking in terms of taking yourself off track from your long-term plan.”

However, he adds that schemes should ensure liability-driven investment managers have at least one UK bank on their derivative trading panel, to mitigate the impact of any loss of passporting rights.

Further flows to CDI strategies?

Successive surveys have predicted the continuing use of LDI to hedge unrewarded rate and inflation risk, and while there are disagreements about schemes’ readiness for cash flow-driven investment strategies, the direction of travel is clear.

Buying out benefits with an insurer requires the majority of assets to be held in government and investment-grade corporate bonds, and self-sufficiency strategies reducing the risk of sponsor cash injections do not look dramatically different.

There are still some questions to consider when setting fixed income strategy.

Managers have sometimes shown a preference for short-duration credit assets in rising rate environments, as this means they can allow bonds to mature and reinvest the proceeds if a rise in gilt yields means they are no longer being adequately compensated for the risk they are taking.

Infrastructure

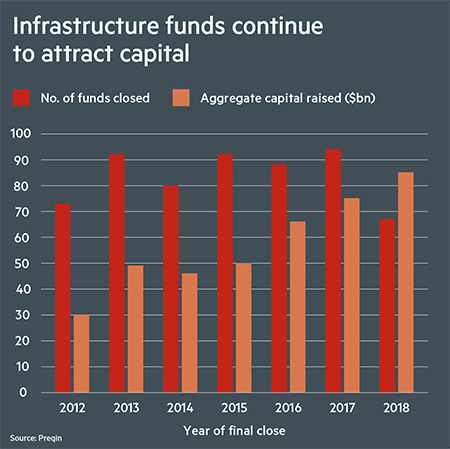

Yield-starved investors have flooded into alternative assets over the past five years, with DB schemes in particular finding that real assets like infrastructure can deliver a stronger cash flow than fixed income, while providing a rough inflation hedge.

That trend does not look to have slowed down, with Preqin global data showing a record-breaking $85bn (£66bn) of aggregate capital raised in 2018, with dry powder reaching a record high of $172bn in December.

Crowding in the asset class could see yields compress further, although MJ Hudson chief executive Odi Lahav says the asset class’s inherent features mean it will stay in many portfolios.

However, Brexit and the recent parliamentary chaos may knock interest in UK illiquid assets, according to investment manager Ingenious.

However, evidence from the market suggests the flip side of 2018’s pain is that yields in spread markets have risen sufficiently for managers to match DB schemes’ projected cash flows using long-dated investment-grade credit with a low risk of default.

“We’ve seen a repricing, a widening of credit spreads,” says Lionel Pernias, head of buy and maintain for London at Axa Investment Managers, explaining that recent volatility has offered his company attractive entry points. “We position ourselves with a long-duration bias across all of the portfolios.”

However, he adds that, in a break from the hunt for yield that characterised recent years, managers in both high-yield and investment-grade markets will have to be picky, lending to companies that can weather the end of the business cycle.

If CDI investing is set to be a dominant trend for DB schemes, some are also appealing for reason. Mr Lewis notes a pickup in US long-dated credit, but cautions: “The thing we’re really strongly against is over-nuancing the cash flow-matching element.”

He prefers to implement a “cash flow-aware” strategy to one that tries to exactly match payments, in part because the largest flows out of schemes, transfers and collateral calls from LDI, are somewhat unpredictable.

Mr Delo backs this call for CDI to be used only where it is truly appropriate: “The real issues may be a way off, and just because the investment management world is flogging product in this area doesn’t mean you should do it.”

Alts provide reasons to be cheerful

Publicly traded fixed income may not be the only way to deliver these cash flows. Schemes have reached into alternatives such as private credit and infrastructure debt in a search for yield, and for many these changes are now baked into strategic asset allocations.

“If spreads are widening in public markets they’re also going to widen in private markets,” says Mr Lahav, adding that many schemes are still decades from full funding on a buyout level. “If [schemes] have shifted into private debt because that was part of the strategy, they aren’t all of a sudden going to shift into investment-grade credit.”

Where public market managers like Mr Pernias are shifting their portfolios towards quality, the ability to delay deployment in illiquids means Mr Lahav sees a reason to be cheerful in forecasts of a recession in the medium term.

Managers in special situations or distressed markets tend to do well from exactly the kind of corporate indebtedness and lax approach to loan covenants that has some economists wringing their hands. “Those are where there is lots of opportunity and you can see that in private equity, in credit, in mezzanine, even in hedge funds,” Mr Lahav says.

Topics

- Alternative assets

- Aviva Investors

- AXA Investment Managers

- Bank of England

- Defined benefit

- Defined contribution

- Derisking

- EPIC Investment Partners

- Equities

- Fixed income

- Hedge funds

- Infrastructure

- Investment

- LCP

- Liability-driven investment (LDI)

- multi-asset credit

- Nest

- Pan Trustees

- Private equity

- Real estate & property

- Redington

- UK equities