Data crunch: For active managers, the ultimate test of mettle will always be whether they can beat their benchmark. As of the end of 2018 the news looks good for stockpickers specialising in UK equities, but analysts say there are still concerns behind the numbers.

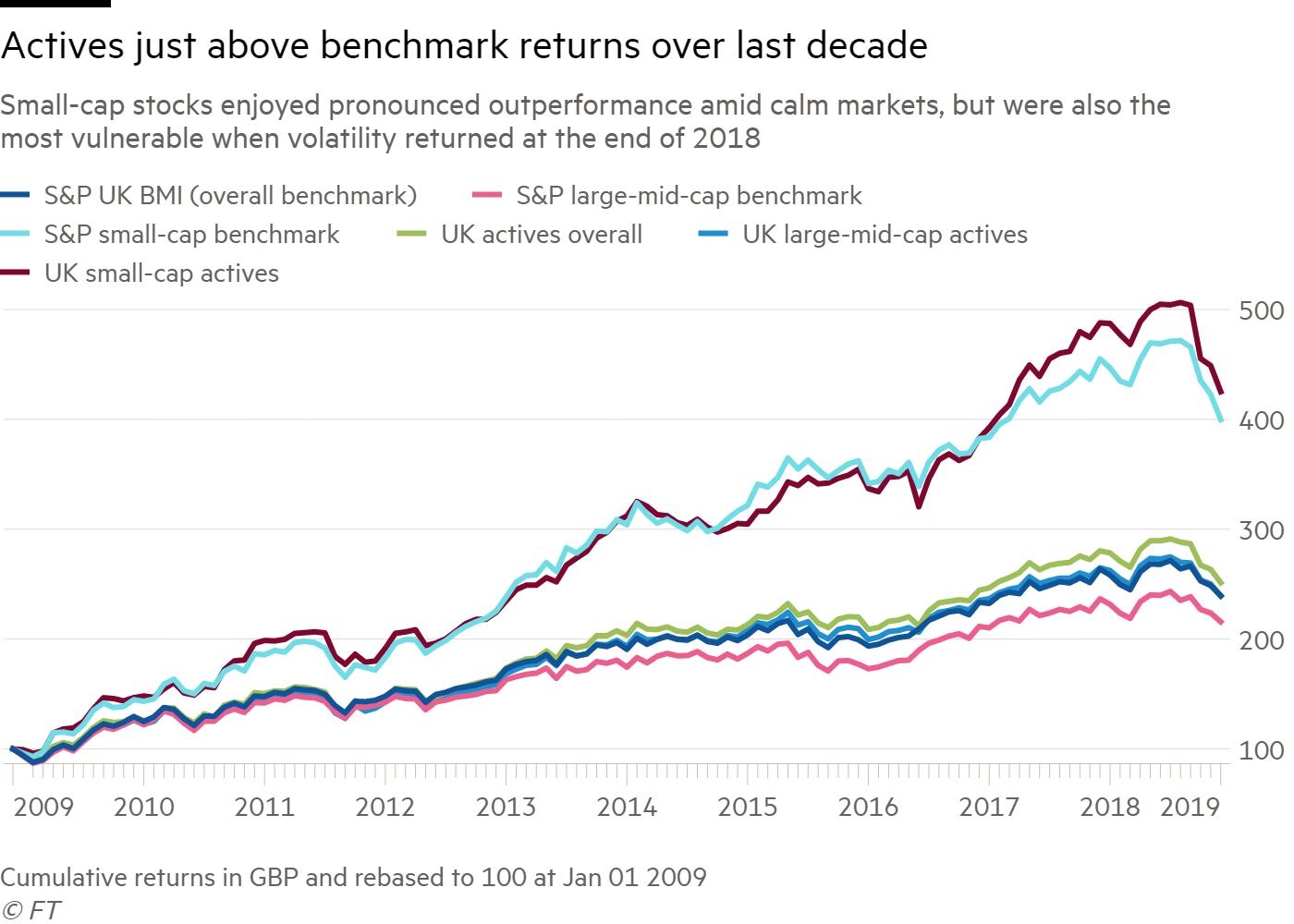

Analysis by S&P Dow Jones Indices shows that over the past 10 years, the average UK equity manager has outperformed the company’s UK BMI index by a small margin, delivering an extra 4 per cent of total return.

The results are asset-weighted to limit the influence of small funds on the average, and crucially do not account for the fees charged on the more expensive active funds.

However, even disregarding the costs of active decision-making, trustees will have to do better than simply picking a middling manager to receive outsized returns.

Over the same 10-year period, 73 per cent of UK active equity funds underperformed the S&P DJI benchmark. The result is similar over 2018 (73.5 per cent), despite the end of the year featuring the return to volatility that actives said would restate their case after years of central bank-influenced calm.

Actives rely on small caps

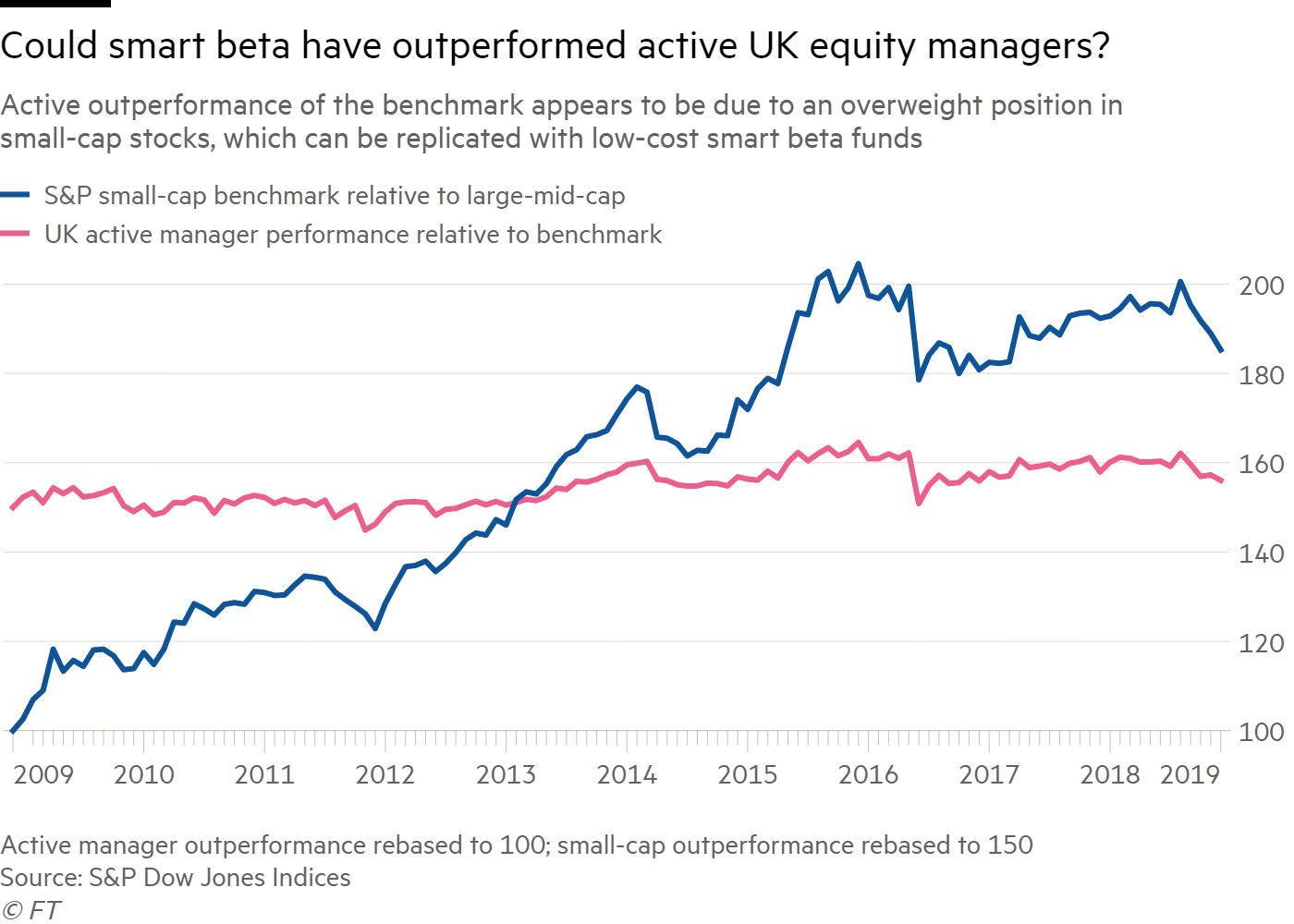

Andrew Innes, an associate director at the index provider, raises a further concern about stockpicker performance, pointing to the similarities between the outperformance of active managers and the outperformance of small-cap stocks versus larger companies.

“This highlights that the typical UK active fund has a smaller company size bias than the broader benchmark index and this bias explains most of the long-term outperformance of the fund category,” he says.

Mr Innes also says this bias towards smaller stocks explains the inability of active funds to neutralise 2018’s year-end volatility, “as the large drawdowns in the market were even more severe among smaller-cap stocks”. He says the evidence points to active managers being poorly prepared for the last quarter of 2018 and “even more susceptible to losses because of their small size biases”.

Small size bias has helped active managers achieve overall outperformance on average over 10 years. But there is a further question over whether this constitutes real alpha, the idiosyncratic return that commands active fees.

“The small size factor has been a relatively stable performer, and one could argue that the returns generated from this factor has, until recently, been disguising (to some degree) the lack of real alpha generated by active managers,” says Mr Innes, adding that a smart beta fund focused on size could theoretically have generated better outperformance with lower fees.

Active has potential to weather downturns

However, some trustees are keeping the faith. Dinesh Visavadia, client director at Independent Trustee Services, says he is seeing schemes return to active management amid concerns about the maturity of the business cycle.

He says boards on which he sits have seen recent results from active managers that in some cases he classes as “pretty phenomenal” in terms of absolute return.

“Active management is the key at the moment in terms of accessing the equity market because… in uncertain markets you want to just pick the winners rather than the lot,” he says.

Comparing average active managers to a benchmark can only be of limited use, since the decisions of stockpickers drive the performance of the benchmark. It is hardly surprising that the average manager will underperform after fees are taken into account.

Still, this also means that unless trustees believe they can pick the best performing managers consistently, they are better off buying average performance via a passive fund, leading Simeon Willis, XPS Pensions' chief investment officer, to follow a strategy of "using passive where passive is a viable option".

"The argument for using active management has often focused around preserving capital in downside events, and some managers have proven ability in that area," he says. "The challenge is doing it in the future, and splitting the ones that did it by luck and those that did it by skill is very very difficult."

Mr Willis stresses that the data do not prove that active managers are doing a good or bad job, but merely that passive products in many markets can track their performance. Active fund managers play an important role in allocating capital in society, but the added cost compared to passive means schemes are better off leaving others to fund this social benefit, he says.

"You want somebody else to do it and your just free-ride off it by investing passively," he says.