Data crunch: Eight years after the auto-enrolment revolution, millions of workers’ pensions are left languishing in master trusts when they move jobs.

Unloved and forgotten pots are a concern for all, but some deferred members in schemes levelling fixed administration charges, such as Now Pensions, could see their pots even vanish without further contributions.

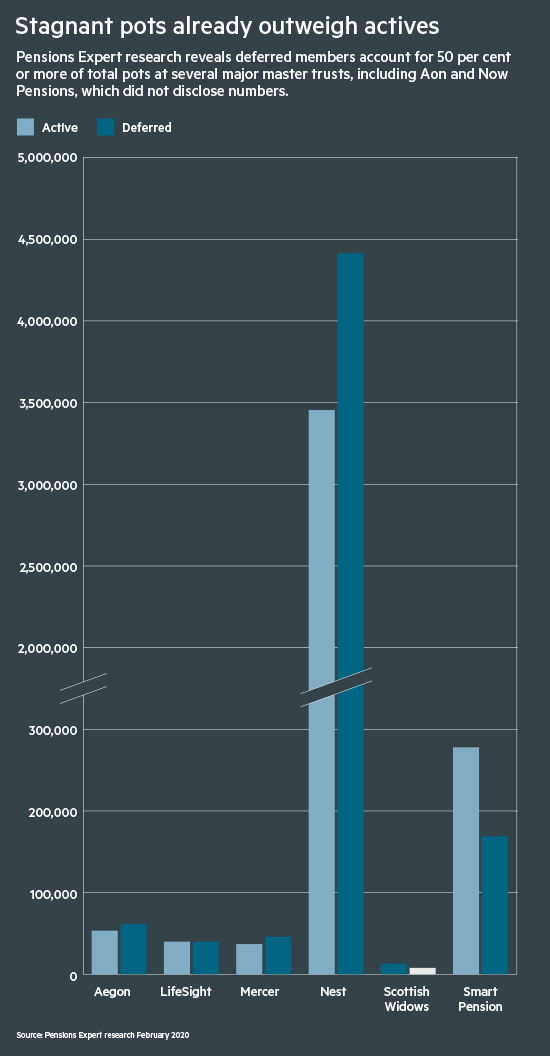

With most people having an average of 11 jobs across their lifetime, the need for reform is increasingly urgent. Indeed, many defined contribution master trusts already have more deferred members than contributing members, as our research shows.

My concerns with any pot-follows-member approach is with the high costs of transfer, which the member will pay

Laura Myers, LCP

Sectors with high staff turnover, such as hospitality and supermarkets, are particularly badly hit. The long-heralded pensions dashboard could offer a solution, but its launch is seemingly some way off and data will initially be far from complete.

Deferreds are expensive to run

For the employer, deferred members can be an unprofitable nuisance. Laura Myers, head of DC at LCP, says: “The problem here is principally one of costs to whoever is paying for the running of the scheme [the master trust or trustee or employer].

“It costs the same in day-to-day to administration whether the pot is small or large, so on a ‘per cent of assets’ basis lots of little pots are more expensive to run than larger ones.”

This can affect innovation and service levels, stresses Alan Emberson, director of workplace solutions at Punter Southall Aspire: “These members have, to an extent, become financially unattractive. In a DC world where expense margins are so slim, it has become economically challenging to offer them the best customer experience or journey.”

The majority of deferred members will not see their funds disappear from fees. As most providers charge annual management fees calculated as a percentage of assets, fees do reduce in scale with pot size, with well-run funds hopefully delivering returns that outpace fees and inflation.

However, Ms Myers says: “There are exceptions to this, and that’s those members that have a pot lingering in a master trust with a fixed flat pound amount fee for admin [for example, Now Pensions uses this model] as when these are applied to small pots they can erode pots to zero.”

Indeed, Now Pensions warns savers on its website that “if you don’t move your money, the charges could mean that eventually you have nothing left in your fund”. It charges 0.3 per cent annually with a monthly administrative charge of £1.50.

Fixing the problem

Other master trusts also incorporate flat fees, but some have taken preventative measures to tackle the small pot disadvantage to members.

Darren Philp, director of policy at Smart Pension, notes: “On schemes where we levy an admin fee in addition to a fund-based annual management charge, we have a £500 de minimis for deferred members.”

Smart Pension’s flat fee cuts out when pots drop below £500. “This ensures member pots can’t deplete to zero,” says Mr Philp. “The £500 was set so that over time member pots should always continue to grow in real terms.”

Now Pensions is also looking at how to fix the problem. With an average deferred pot size of just £350 in the master trust, it has looked at a more radical solution that could achieve scale – avoiding either members or providers taking a hit.

Now Pensions director of policy Adrian Boulding told Pensions Expert on December 4 that the master trust is seeking to take matters into its own hands by striking agreements with competitors.

“The idea is that we would use the existing legislation for bulk transfers without consent, which allows the trustees of a master trust to move people without their consent to another master trust,” he said.

Under the plans, if trustees of both schemes could agree that members would be better served by consolidating their savings with their current employer’s provider, the transfer would be made, subject to an opt-out by the member.

Ian Neale, director at Aries, enthuses over the idea: “The strategy for addressing this problem put forward by Now Pensions certainly has merit – and given the Pensions Regulator’s drive to consolidate DC arrangements, I imagine they might think so too.”

Competitors also seem willing to collaborate on the idea, which has reportedly grown out of discussions hosted by a Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association working group.

Roger Breeden, a partner at Mercer, says: “It’s also good for members who don’t have the confidence or inclination to consolidate. It needs to be done on a low-cost basis, so that transitions don’t erode the funds even further.”

David Bird, head of proposition development at Willis Towers Watson’s Lifesight, agrees: “Approaches that make sensible consolidation the easiest route for a member are good and to be encouraged, as long as members are able to opt out and make their own decision if they wish.”

However, the solution is not without its difficulties. Gregg McClymont, director of policy at The People’s Pension, notes that the idea “has potential, but there are a series of difficult technical and governance challenges”. He urges the government to prioritise solving these issues.

Tony Pugh, Emea DC solutions leader at Aon, sees a potential spanner in the works: “What if the services under the new plan are not as good or the investments are inferior? What if the new plan charges are higher?

“As a member I wouldn’t be happy for this to happen, and even if there was an opt-out option, most members are disengaged and wouldn’t use it.”

Ms Myers endorses this view: “My concerns with any pot-follows-member approach is with the high costs of transfer, which the member will pay.”

Ferdy Lovett, partner at Sackers, adds: “You need a regulatory framework for this for trustees to have comfort that what they are doing is consistent with their duties as trustees.”