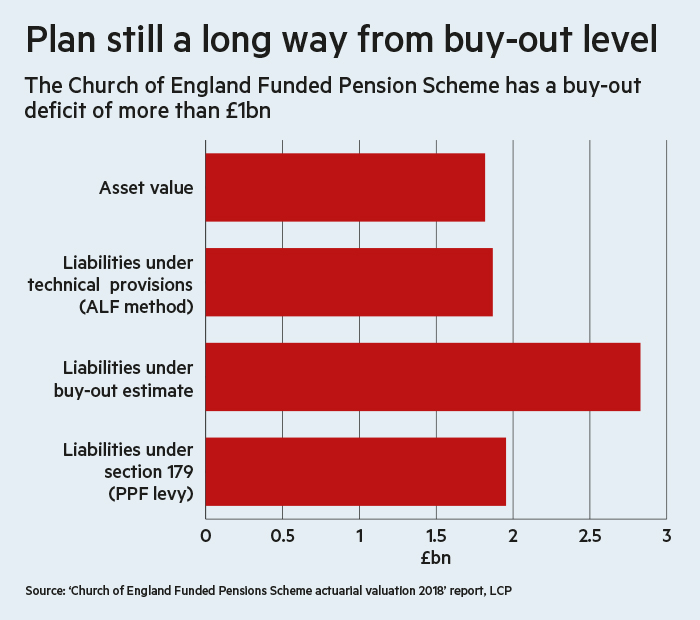

The Pensions Regulator has dismissed the idea of the Church of England reducing its deficit contributions, after a change in the valuation method used for one of its defined benefit schemes resulted in a dramatic shortfall decrease.

The Church’s pensions board recently developed a new valuation methodology known as asset-led funding, for the Church of England Funded Pensions Scheme – an open defined benefit fund for clergy with 20,520 members.

The project, which links the discount rate to the assets held by the scheme and was carried out with advisers LCP, led to its deficit reducing from £236m to £50m.

This better reflects the final salary plan’s long-term investment strategy, and helps limit future funding volatility, the board said in a consultation document issued in October 2019.

Employers should pay up front as much as they can, as long as they can afford it. This way, the pension scheme will have more flexibility in case things go wrong

Hugh Nolan, Spence & Partners

It also meant that the contributions required by the 2015 valuation, which would have seen a £236m deficit cleared by December 2025, would instead clear the shortfall two years earlier.

This had led some of the responsible bodies treated as separate employers within the Church to ask whether they could reduce their cash injections from the previous 39.9 per cent of salary, keeping the scheme on track for full funding in 2025.

TPR prefers shorter timeline

However, the regulator, which has been taking a greater interest in the scheme since the 2015 valuation when it first became actively involved, also dismissed this idea.

The regulator stated: “Whereas we recognise that there is a significant level of support within the participating employers to see a reduction to the present 39.9 per cent contribution level, it would be TPR’s preference that the scheme continues to reduce the present deficit in as short a time period as possible.”

The watchdog noted that if the contribution rate was to be reduced, it would need to “understand the reasons for the reduction and how the risks of the reduction would be managed or mitigated”.

Lincoln Pensions, the pension scheme’s covenant advisers, also noted that clearing the deficit as quickly as possible would be more beneficial to members and, ultimately, to the fund’s responsible bodies. Furthermore, a small reduction in the contribution rate would not strengthen the overall covenant rating, it added.

In a summary of the valuation report, LCP noted that if the previous method had been continued, employer contributions would have had to rise dramatically.

In general, where a scheme’s deficit reduces, the regulator prefers to see deficit-recovery contribution rates maintained – with consequently shorter recovery periods – rather than lower deficit contribution rates paid over the same period, it added.

Hugh Nolan, director at Spence & Partners, notes that the regulator’s point of view is “always to pay any deficit as quickly as possible to secure member benefits”.

He says that while the change in methodology produced a lower deficit figure, there is always a risk that these assumptions are wrong and that the deficit “could still be the previous £236m”.

“This means that employers should pay up front as much as they can, as long as they can afford it. This way, the pension scheme will have more flexibility in case things go wrong,” he adds.

TPR data indicates the median recovery plan length to be seven years and, according to its annual funding statement for DB schemes, published in March 2019, “schemes with strong covenants should generally have recovery plan lengths that are significantly shorter than this”.

Lower contribution rate in 2023

After requests from stakeholders in response to the consultation, the Church of England Pensions Board also reviewed the new valuation methodology with LCP, which allowed the Church to reduce the deficit further to £50m and clear it one year earlier, by the end of 2022.

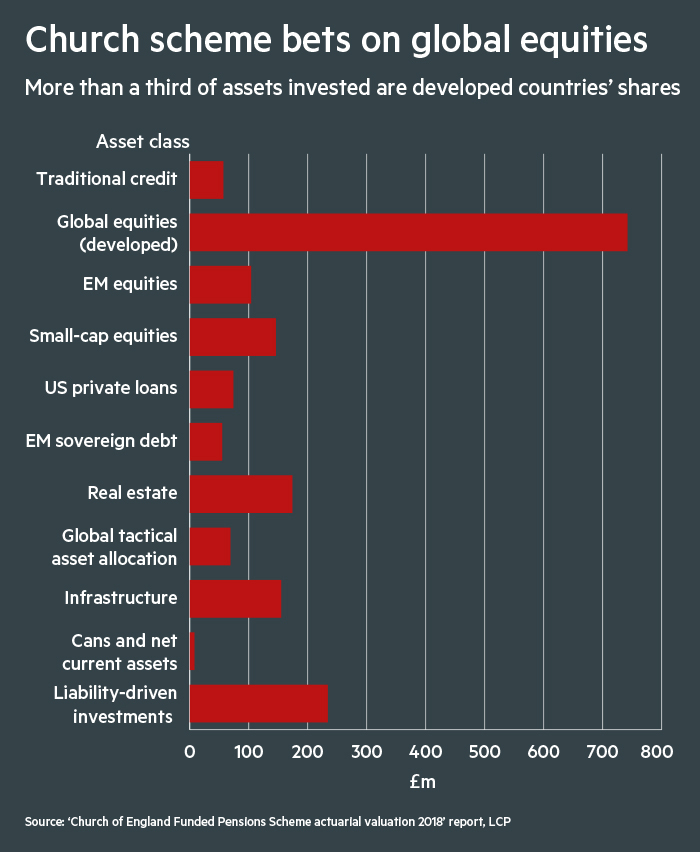

Aaron Punwani, partner at LCP and the scheme’s actuary, notes that the pension fund is in an unusual position, since it “is a large scheme that is open to new members, and has a policy of investing a higher proportion of its assets in long-dated illiquid investments and less in gilts than the typical scheme”.

He says: “This lends itself to the use of the asset-led funding method, whereby the investment return assumptions are driven from the yields on the investments the scheme expects to hold over the long term, rather than purely from gilt yields.

TPR: 700 DB schemes may never reach full funding

Forty-nine defined benefit schemes are in a parlous state with funding under 50 per cent of their liabilities, the latest data from the Pensions Regulator reveals.

“This closer alignment between the investment strategy and the actuarial valuation should result in a more stable funding position over time.”

If the estimates for the deficit are met, the Church of England expects that the contribution rate from January 2023 will reduce to 32.8 per cent for future service.

The board said: “However, we are still in turbulent financial times, and we do not know what Brexit will mean for pensions and wider economic conditions.”