Data crunch: Companies with large defined benefit pension deficits risk seeing their share price drop as investors stay away, after equity analysts raised questions over whether their pension plans need urgent topping up.

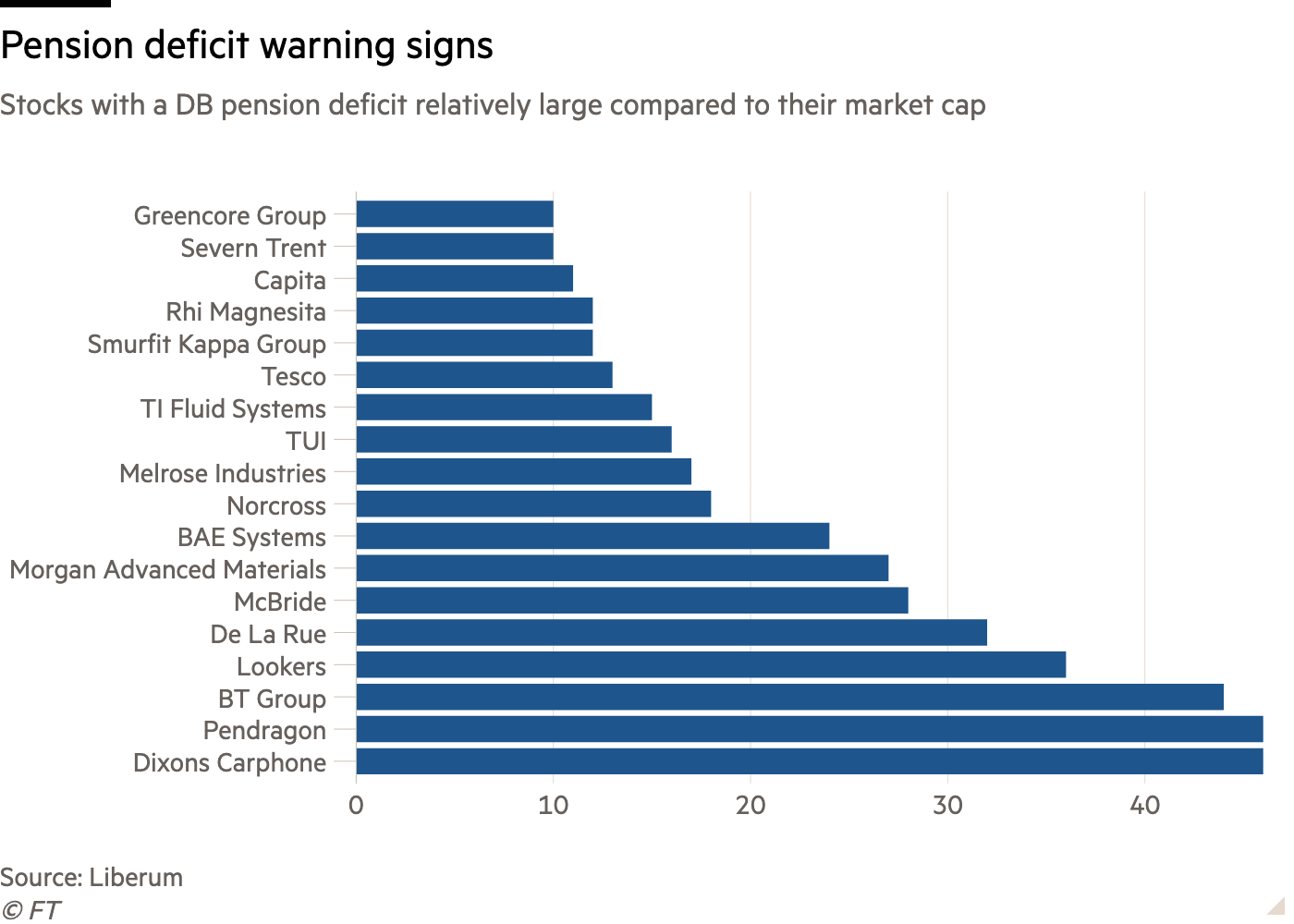

A screening of the FTSE All Share Index by Liberum reveals the companies with deficits that are worryingly large relative to their market capitalisation.

The findings show 18 stocks with pension deficits exceeding 10 per cent of the market value of their outstanding shares. Dixons Carphone tops the list, with underfunded promises worth 46 per cent of its total equity.

You can be pretty sure that those companies will be under close scrutiny by the Pensions Regulator

Charles Cowling, Mercer

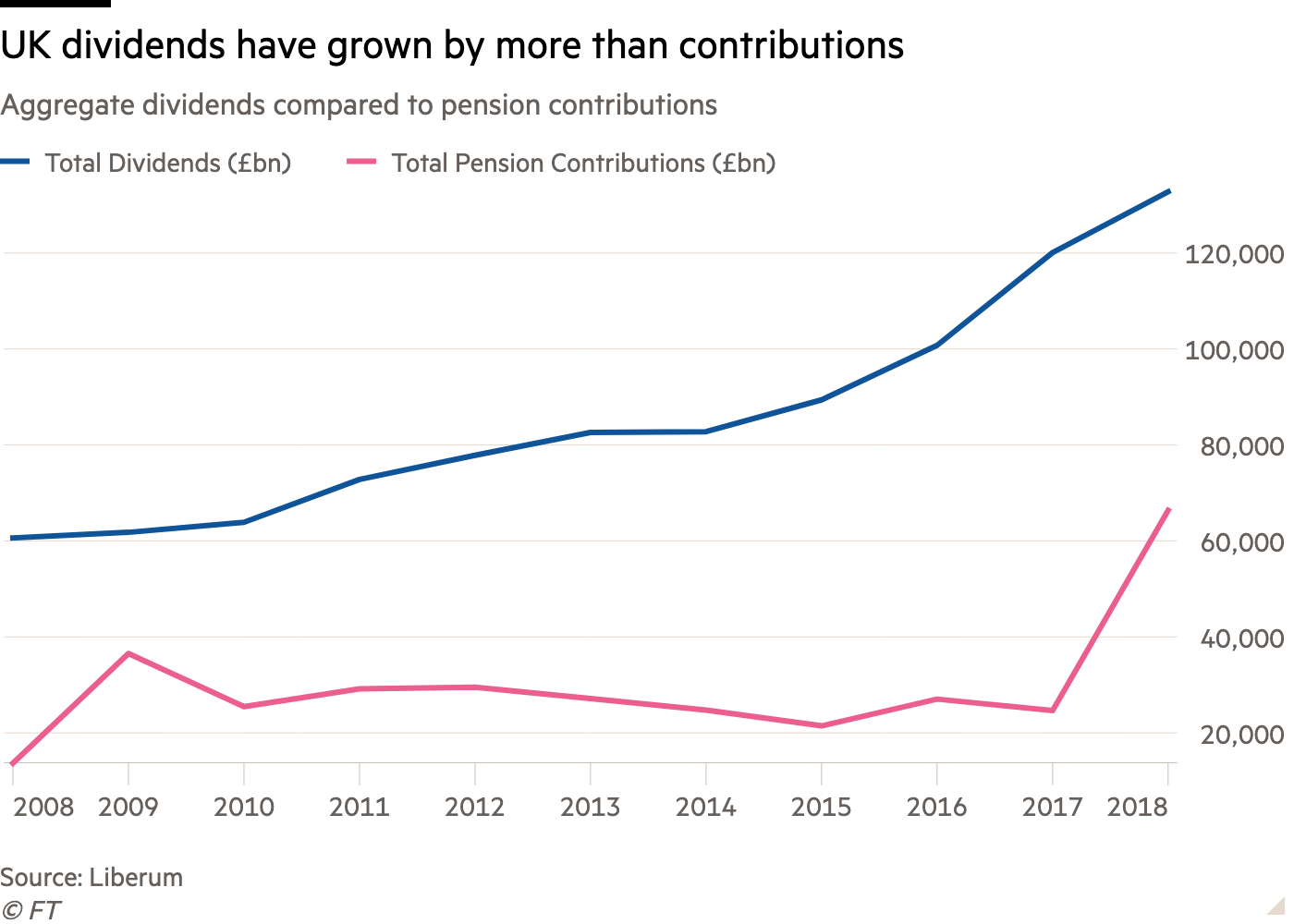

While these companies made both dividend and pension contribution payments over the past five years, payments to dividends were larger than their pension contributions, and relatively large compared with their overall equity.

The data suggest these companies could struggle to pay out their pension promises in the future if they do not top up contributions, according to the author of the report, Liberum’s equity strategy analyst Andrew Coury.

Impact on share price

Investors have become increasingly aware of funding statuses in the wake of high-profile defaults, including big-name collapses such as Carillion, BHS and House of Fraser, explains Mr Coury in the report.

This suggests shareholders are growing wary of stocks with comparatively large pension deficits.

Commenting on the figures, Liam Mayne, partner at Barnett Waddingham, says these pension schemes are likely absorbing a significant amount of cash from their sponsoring business, even relative to what shareholders are earning.

He says: “The significance of this is that if the pension deficit of such a company worsened then it is likely to have a significant impact on what shareholders can expect to earn.

“It also means that if the business underperforms then it may have to cut shareholder payments substantially in order to maintain pension deficit contributions.”

While the data screened for stocks with a pension deficit at least 10 per cent of market cap, a handful had pension deficits worth almost half the size of the value of the company.

“To put it into context, Carillion had a deficit that was around 4.5 times its market cap before it issued a warning,” says Mr Coury.

“The list shows current deficits are relatively smaller – however, there is a concentration of companies that have comparatively high deficits.”

He adds: “Given the size of the deficit relative to its market cap, the question is are the companies looking out for themselves or the scheme members?”

According to Charles Cowling, chief actuary at Mercer, some investors will steer clear of companies with big pension issues.

He says: “Shareholders are wary of the size of the investment risk, the size of the pension scheme, and they are wary of the size of the deficit; all of these things affect company share prices.”

He continues: “At a very base level, it is a real problem and that is why there is an imperative on companies to try and sort out the funding of their pension schemes, because shareholders are quite reasonably nervous about such large financially challenging positions.”

He adds: “What you will find is that for those companies at the top [of that table] pensions will be on the board agenda, and they will be managing the pension scheme as closely as other key parts of their business.”

Measurements of risk are approximate

The figures used in the analysis are based on company filings – accounting measures – rather than the actuarial valuations used in triennial reviews.

“The accounting and actuarial measures for a pension’s funded status can vary materially,” explains Mr Coury.

“It would also be important to look at what the scheme’s assets have done, if they have underperformed etc, but we do not have visibility on that,” he adds.

According to Barnett Waddingham’s Mr Mayne, the ratio of funded status versus market cap is “a relatively simplistic measure” of the balance between shareholders, business and pension members.

He suggests this is because businesses with a high pension deficit will likely be very active in managing the pension problem, given the potential impact on shareholder payments if it does not.

He continues: “Like any metric, it has pros and cons… it does not tell you if the pension scheme could become a significant issue for management.

“For this, you need to understand the absolute size of the assets and liabilities of the pension scheme, not just the difference between the two.”

Similarly, Marian Elliott, managing director at Redington, suggests a pension deficit might be high relative to the size of the company’s equity as a result of corporate transactions, historic investment and hedging strategies, or a reduction in the size of the company over time in the normal run of business.

She continues: “We work with several schemes where the size of the deficit used to be high relative to the sponsor, but they have managed to reduce this significantly and have a viable plan in place to return to full funding without undue reliance on the employer.”

Companies can expect regulatory intervention

Indeed, the Pensions Regulator has been vocal about companies not prioritising dividends over pension contributions.

“You can be pretty sure that those companies will be under close scrutiny by the Pensions Regulator because if the risk signs are there the regulator wants to be close to the discussions between the employer and the trustee on how much money is going into the pension scheme,” says Mr Cowling.

Mr Cowling adds: “If companies want to put up dividends, if they have pension scheme issues, then they better be putting up pension contributions as well.”

While TPR has yet to define an absolute funded status limit for regulatory intervention, it is clearly continuing to focus on dividends and other cash returns to investors versus payments to the pension scheme.