Five defined contribution experts discuss default pathways, striking a balance between flexibility and secure income, and the importance of guidance at retirement.

Earlier this year, the Work and Pensions Committee called for the development of default retirement pathways. What progress needs to be made when it comes to at-retirement innovation?

Alistair Byrne: We know that defined contribution scheme members value the pension freedoms, but find the required decisions complex and confusing. Default pathways can help individuals navigate and make the most of the available options.

Unlike for the saving phase, it is difficult to have a default at retirement that involves no input at all from the member. The key thing is to streamline and simplify the decisions to be made. Once the member has a broad idea of what he or she is looking to do, the process should be made as straightforward as possible. For example, members wanting to use drawdown will value well-governed default investment strategies and guidance on sustainable withdrawal rates, rather than having to figure it out themselves.

In an ideal world, all members would receive personalised advice on their retirement income options, but this is unlikely in reality.

Maria Nazarova-Doyle: DC has only really taken off in the UK on the back of auto-enrolment. This is still a very ‘young’ area but one that is growing exponentially. Most people will not rely on DC savings if they come up to retirement in the next few years, as a lot of people would still have defined benefit pensions as well.

However, in the next few years we will see this pattern shifting. As pots grow and their importance and share in the overall individual’s wealth increases, more and more people will need to be able to use these savings to draw sustainable income.

The good news is, we still have a few years to get our act together as an industry and create products that will help facilitate this. The bad news is that we have not done much to date and the level of innovation just has not been as high as one may expect in an area of such strategic importance. One of the key factors that will drive innovation in this space is if mastertrust Nest is ‘unchained’ to create new drawdown products. If their retirement blueprint, launched a few years ago, is anything to go by, this is definitely the space to watch.

Naomi L’Estrange: For me, this is one of the biggest issues. Government needs to give providers both a carrot and stick to ensure they put in place appropriate and good value default pathways, not only during the growth phase but during and after the retirement process. Some schemes have broadly acceptable defaults but most leave their members or customers entirely on their own, or facing unacceptable charges, at or after retirement. Proper lifetime pathways are already developed or available, but in my experience mainly in a workplace context where the trustee and sponsor has had the vision and leverage to require it – providers need to be encouraged to extend this to the wider market, by intervention if need be.

Trustees and providers also struggle with the legal aspects of moving members into a new more appropriate default without consent. This risk is perhaps overstated. Detailed and consistent guidance on this from the Financial Conduct Authority and the Pensions Regulator would be extremely helpful.

Laura Myers: As an industry, we need to see more innovation at retirement and I am hopeful that default retirement pathways will be the start of that. Typically, members with small to mid-sized DC pots will not choose to take advice from an independent financial adviser, so pension providers offering sensible default pathways will help members grow their retirement savings into sustainable income, without having to manage their own money.

Without innovation, retirees could end up in sub-optimal strategies; either by taking excessive risk or being unduly cautious. Most retirees have not actively managed finances between different asset classes, so how can we expect them to suddenly conjure these skills? Members need easily comparable drawdown products so they can assess the basic differences in the same way they would buy life insurance or a mortgage.

I do have concerns about members being defaulted into drawdown products without taking personalised advice, but I also feel that ensuring retirement products are regulated under the same governance and cost controls as pension accumulation products can only be a good thing. However, to ensure savers are not pushed into inappropriate products, further effort is needed to educate savers.

Dianne Day: Once a member reaches the pre-retirement phase, the focus moves from the collective nature of the default fund to the individual’s unique retirement circumstances and timing. There are many unknown, personal variables at play at retirement, so setting an appropriate default pathway is challenging.

Members now have increased choices from age 55 onwards, so guidance and decision-making support is a priority. This could be in the form of professional advice or achieved through online support tools and education. Recognising the need for a customised approach, members need help to choose the right retirement strategy, rather than the right product, provider or investment option. Progress and innovation in this area has the potential to boost outcomes.

Initiatives aimed at consolidating multiple inactive DC accounts will also help members to take control of their retirement planning.

The default investment design will depend, as always, on the choices and trade-offs between investments that offer fixed outcomes and fluctuating but potentially inflation-beating outcomes. The right retirement strategy for a member may include a combination of these options over time. In the absence of any other member details, projected life expectancy suggests that a reasonable level of continued exposure to growth assets for both inflation hedging and income growth is appropriate.

What can policymakers do to boost outcomes for non-advised drawdown investors?

Myers: Right now, engagement starts much too late for most members. This could be the most important financial decision of a member’s lifetime, so we need to see better member journeys being supported by a stream of digestible education spread over a much longer period of time. When we work with our DC clients to improve their members’ experiences as they move towards retirement, we find we get much better engagement by providing education as bite-sized nuggets that increase in size and frequency as the members approach their target retirement age.

Administrators and providers can also help here by providing very simple paperwork and communications; retirement packs are just overwhelming. And the situation is even worse when you consider that most members have several pensions and so receive several retirement information packs.

We also need to see more cost-effective guidance and advice – the vast majority of workplace members do not have advisers. While the robo-advice industry continues to develop, I think that more low-cost solutions would help boost member outcomes.

Day: I have noticed a change in the terms used by pension providers in their retirement communications lately, where they refer to ‘members’ in the accumulation phase but start calling their customers ‘investors’ in the pre-retirement phase. This is an important cue: having been in a default to date, members need to start taking personal responsibility for their pre-retirement planning and decisions. Messaging that triggers earlier involvement in people’s own retirement planning can change attitudes and increase involvement.

Some schemes are now using drawdown as their default, which is possibly not well suited to members who are used to having the investment thinking done for them. There needs to be more careful consideration by trustees and those selecting defaults as to whether this is really the best option and if so, providing more help at the beginning and along the way.

Even if those in drawdown did not take advice or guidance initially, a regular check-up needs to be offered repeatedly – like the ongoing servicing and certification of a boiler. Providers need to remind investors that drawdown is not a ‘set and forget’ retirement option. The development of interactive online accounts to manage drawdown is vital, as well as better integration with other aspects of a retiree’s financial life, such as banking, benefits and tax.

Nazarova-Doyle: An average pot that is being invested in drawdown funds has been estimated at circa £70,000 just a few years since the introduction of pension freedoms, and this amount will only grow with time. For pot sizes of this magnitude, most providers offer easy access to a drawdown facility and a default investment option that does not require advice. For extremely high savings, the advisory market is there and is accessible (for a fee).

The industry has been working hard to educate savers for a number of years now, and this is a continuous effort and one that will hopefully start to bear fruit once the savings are sufficient for people to start paying more attention.

The bottom line is, for a number of people, using a drawdown facility from their default arrangement may be an appropriate and efficient way of receiving income. Also, as the pots grow, the relative value of individual advice will also grow. Granted, more innovation is needed in this market but right now I do not see this area as the biggest concern in DC.

Byrne: The pension freedoms have dramatically widened the market for drawdown. Previously, the typical drawdown customer had substantial retirement savings and an ongoing relationship with an adviser.

Now, there is a mass market of less experienced investors, with less access to advice. Default pathways are a key element of the solution – simplifying the decision making. Our research also finds that people who consult Pension Wise tend to value the guidance they received, but relatively few people take advantage of the service or do so early enough in the decision-making process. So, there is a need to improve take-up of this useful service, which is due to be merged with the Pensions Advisory Service and the Money Advice Service to form a single financial guidance body. There also needs to be continued innovation of advice models, such as the use of robo-advice. This will not suit everyone, but it has a role to play.

L’Estrange: At the lower/mid-size of pot, design, not advice, is the answer. Ideally, we need simple low cost drawdown products with default investment strategies, where withdrawal of cash is easy up to a ‘safe’ limit and beyond that requires a 15-page form. Inertia will do the rest.

Survival pessimism can lead individuals to be insufficiently prepared for retirement. How can a balance be struck between flexibility and secure income?

Day: It is human nature that we find planning difficult when it comes to events a long time in the future. Research suggests that most members start planning for retirement around two years out. This is in contrast to the pre-retirement phase of most pension schemes, which start derisking five to 15 years out – recognising the risks of a substantial correction in markets and the member’s reduced capacity later in life to recover lost capital through savings from salary and wages. Trustees must manage pensions towards their long-term outcomes, even if members’ time horizons and attitudes are not always aligned.

The issue of time horizons is the key to balancing flexibility and income security during retirement. It is likely that members will be offered a wider variety of investments to suit their changing needs as retirement account providers innovate. Direct investments such as term deposits, term annuities and exchange-traded funds may sit alongside more conventional managed retirement investments. In the future, new pensions players – including banks and fintech firms – may provide more holistic retirement accounts to the product solutions we think of today.

One of the biggest challenges is how to fund the later stages of retirement as care home fees, now averaging between £750 and £1,000 per week, rise. This will burn through any equity retirees have in their homes quite quickly. Based on average time in a care home, should individuals be targeting investments that produce this income? Will the state pick up when they run out of capital?

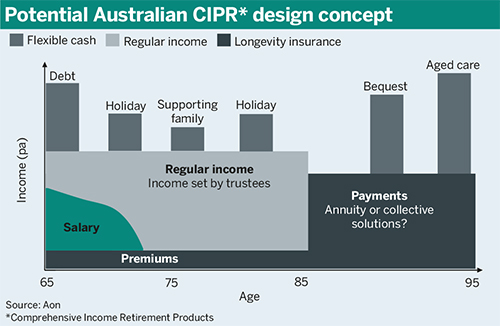

Nazarova-Doyle: We need products that will have features of both drawdown and annuities. Savers need flexibility, particularly during the earlier years of retirement.

Towards the later part they need certainty and protection from extreme poverty at the time when they often have neither the physical nor mental facilities to support themselves in other ways. A simple way of securing this structure would be buying a deferred annuity at the point of retirement that kicks in around age 80 or later to provide insurance from the longevity risk, while the rest of the savings could be used in a flexible way to bridge the gap up to that point. If not doing exactly this, we need products that try to replicate this sort of scenario in order to let the retirees have their cake and eat it. Again, savings need to increase significantly from current levels to make these solutions viable income options.

Byrne: We do find that individuals tend to underestimate how long they can expect to live, and this has implications for effective retirement planning. Equally, members understand there is a risk they will outlive their savings and thus can be motivated to insure against this risk.

There is value in combining flexible income drawdown in the early years of retirement with secure income provided by a deferred annuity payable from, say, age 80. The drawdown problem becomes simpler – with savers considering, ‘How do I make my assets last from retirement to age 80, rather than for an indefinite period?’ The alternative is ‘self-insurance’, whereby individuals underspend for fear of running out of money in later life. The market for deferred annuities is very limited, but it may develop if demand is forthcoming.

Myers: I expect we will see more products in future that combine drawdown-style features with the security of annuities. Members do want some level of guaranteed income, but they want flexibility too – ideally in a packaged product that is simple to understand and cost effective for the mass market. One example here could be products that have, or advice and guidance that recommends, partial annuitisiation at age 65 and only using drawdown for five to 15 years before fully annuitising. There are benefits to combining annuities and drawdown.

Research by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries has shown that using this type of strategy is likely to provide retirees with not only higher incomes (compared to drawdown alone), but also lower risk. It dramatically reduces the risk of running out of money later in retirement – a risk that is prevalent if members take the wrong level of income from a drawdown-only product or take that income at the wrong time. Another similar variation of this strategy is using the flexibility of drawdown in the younger years of retirement, when this flexibility may be of greater benefit, and then locking in some security later by buying an annuity.